Creating a rubric for an activity, presentation, or paper? It’s daunting. A dozen years into teaching, and I often stare at the screen, fearful of not getting it right.

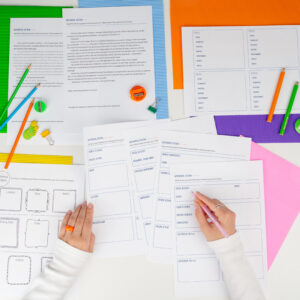

Today, we’re talking rubrics! I primarily use rubrics with papers and public speaking. I do provide rubrics with one-pagers and literature activities, but the rubrics for writing and speaking stress me the most. Those projects are typically of high-point value, and I realize that multiple people will be looking at them.

Which. . . is good! I want students to know my expectations and read over them. I beg my students to allow a sibling, parent, or tutor to read papers and watch speeches. Still, I am aware that a rubric I hand my students will find itself in other hands. Rubrics need to be accurate and polished. They should also be fair to students and meet standards. ELA rubrics are vast and require lots of thought.

What is a rubric and why is it important?

A rubric is a scoring guide that clearly outlines the expectations and criteria for a particular assignment or task. It is important because it provides a standardized and transparent way to assess and evaluate student performance, ensuring fair grading and providing valuable feedback for improvement.

Overall, rubrics require a great deal of detail concerning learning outcomes, learning objectives, standards, and other specific criteria. The longer you teach, the more comfortable you will be with developing a language arts rubric.

Sometimes looking at another teacher’s process helps my process. Here’s my method for creating a rubric.

Plan your rubrics ahead of time.

Plan on creating a rubric as you write the assignment sheet for students. For instance, when I assign a narrative writing project, I know that on the assignment sheet I will stress how students are to connect the writing and research to their communities. The rubric needs to reflect that goal.

When I consider rubric language, I want students to understand the terms. Yes, I look at the standards and work toward meeting those. Overall, students don’t understand the complexity of standards, so my language is user-friendly. I don’t want the expectations to intimidate my students—my writers and public speakers should understand the assessment.

Next, students should have the rubric as they work so that they understand the assessment. As the teacher, providing the rubric ahead of the due date is a must. Encourage students to consult the rubric when they feel they are finished with that paper or assignment. Often, I model that with students. I pull out the rubric and talk through the draft with students. Is the paper completed? Are there areas for improvement? Probably. Model and help students visualize how to improve their writing.

I actually think getting the rubric to students and encouraging students to consult it is teaching students life skills. When they are older, they will have expectations, but a boss or college professor may not hand them a “rubric.” Understanding expectations and then designing a project is a common life event. Ask students to consult the rubric! This helps students understand expectations.

Start simple with basic descriptors.

You’re getting the rubric done ahead of time… great. Now, don’t stress and keep it simple. Those first few years of teaching, be aware that you will mold and shape your rubrics for some time.

For the first run with students completing an assignment, I find it best to create a simple rubric. My expectation for an ‘A’ assignment will be the main point, sometimes the only point, a single-point rubric. I then deduct points as necessary.

As I continue teaching, I modify the rubric fewer and fewer times. However, I often find ways to improve my wording or clarify the expectations.

After the first use with a rubric, I then decide if I want more details. I know I will change a rubric multiple times! Doing so is not a negative. We grow as teachers, we learn more about our communities, and we learn new research. Consider the modification of rubrics a strength. Because I kept the original rubric simple, I can look at where I want to improve the rubric for next time.

Develop rubrics over time.

Those simple rubrics? Be ready to reflect on all ELA rubrics you make. You might keep your rubrics simple, but you might find points that need expounded upon.

I tinker with rubrics, forever. Part of this change is because I experience the strengths and struggles of teaching a concept to a variety of students. Over time, I see the areas where students have opportunities to grow. If I set the bar high and no one reaches it, well, perhaps my expectations are wrong.

So! At first, I have a very simple rubric. Once I am confident in outlining each points column, I do that. With a new project, I rarely have points assigned with specific columns. I make a one point rubric and deduct as necessary.

For instance, I have taught the research paper countless times. I can provide students an accurate description of each stage of a paper. Still, I leave those writing rubrics editable because I want to reflect and grow as I teach. As you grade student writing, you can keep a copy of an extra rubric for you. Add and subtract as you grade students’ writing, perfecting the rubric as you grade.

Give students a voice.

Before I begin assignments, I typically hand students a rubric. This allows everyone to know the expectations, goals of the assignment, and the rubric language. Parents appreciate rubrics, as do counselors and tutors. Additionally, I use rubrics to review domain-specific vocabulary.

Sometimes, however, I include a portion for “student goals” on the list. In public speaking, students create their own goals. Every students creates a goal that will address personal concerns: using fewer fillers, implementing meaningful hand gestures, purposefully moving. I keep a “goal” spot on the rubric, and I look at growth for that goal as students speak. Students have a a say in their rubric, and they find the experience meaningful.

Review grading criteria through the process.

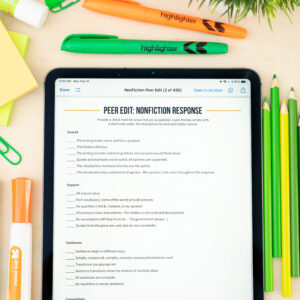

A good rubric can work for peer feedback. Set parameters and guidelines for peer feedback, and review the rubric. Students can then become scorers and provide detailed feedback and then teachers can rotate through peer editing and scaffold understanding, support reviewers, and generally provide feedback.

With older students, levels of achievement become complex. Advancing through education, students must become independent learners. They must ask for help and seek guidance from others. Model for students how to interact with peers, how to give feedback, and how to ask for support.

Peer editing with a rubric is the perfect time to remind learners the purpose of the student work is more than letter grades.

Return to the assignment sheet after grading and assessment.

As my rubrics change and grow, I always return to the assignment sheet. Are my directions specific enough? Did I provide students enough background information for students? If I am holding a rubric which outlines my final expectations, then I need to look at the tools I provided for students to meet standards.

One area where I find rubrics particularly useful is in teaching the research paper. While I provide students with an accurate description of each stage, I keep the writing rubrics editable so that I can reflect and grow as I teach. As you grade student writing, it’s helpful to keep a copy of an extra rub

Finally, I reflect and return to the standards. After I grade a project with my rubric, I evaluate my notes and look at my lessons. Even though this is a difficult step, I add and change material at the end of units. If I wait until I teach a lesson again, I might not understand my notes of I might forget.

Give clarity in feedback.

Once upon a time, I gave high school students way too much feedback. My intention was to help them, to show critical thinking about their writing. Instead, in reflection, I overwhelmed too many young writers.

Now, my job as the “grader” is to give descriptive labels that students can address. Here is an example: Student work shows that the writer needs to work on organization, complete sentences, and descriptive language. Those terms might suffice, but I have found more consistent feedback might be: consider transitions, comma splices, and verb use.

Then—young writers can improve their performance level because they know exactly what areas to focus. In our class discussions, we use those terms (transitions, comma splices, verb use), so they can return to their notes and formative assessments to improve. Consistency and clarity in feedback makes the rubric meaningful.

Talk about the rubric.

After I grade the assignment, I provide time for students to look at the rubric. Sometimes, I conference with each student and outline areas for growth. I don’t return the graded rubric and expect students to look at it. I remind them and purposefully carve time to look at the point. Some teachers call this “delaying the grade” and do not release grades until students understand their feedback.

Creating and using a rubric is part of teaching. Sometimes we teachers don’t have time to reflect on more of the common practices of our jobs. I hope that the insight into my creative method helps you.

Looking for more ideas about rubrics? Melissa at Reading and Writing Haven shares her ways of using them here.