Grammatical terms and patterns cannot be covered through one lesson plan or unit, so they should be taught through a continuum of discussion and gradual advancement of difficulty. First, if grammar lessons only focus on correct grammar, you might discourage young writers.

Second, ELA teachers might think that grammar is separate from the rest of a language arts curriculum. Other times, teachers believe that they should only connect grammar to writing in the situation of grammatical errors.

I’ve found both of those thoughts to be misconceptions. Teaching grammar alongside literature, public speaking, and information texts throughout the school year allows students to see the information in a new form. Teaching grammar in “ten minutes a day” might seem nice because you will have addressed the teaching standards. Students won’t carry grammar lessons to other parts of class if we are busy separating it and only teaching it ten minutes a day.

Absolutely grammar should connect to writing, but when we teachers frame grammar as a tool rather than an issue to be solved, students will take a greater interest in it.

Because English grammar is in all parts of writing and reading, use complete immersion for teaching. Follow Bloom’s Taxonomy as you introduce concepts of English grammar. (I have roughly included both forms of Bloom’s, just to help out other teachers. I’ve combined the final two stages, as they often overlap.)

Along the way, I added talking points. Feel free to use these examples with your students. As your grammar instruction becomes more practiced, you’ll be thinking of your own examples in no time!

Knowledge/Remembering

Acknowledge that students already possess knowledge of grammar even though they may not know it. Students who read and write have an understanding of English grammar, such as parts of speech and parts of a sentence. All lessons benefit by capitalizing on prior knowledge, and grammar is no different. Stress that students do understand pieces of grammar. Automatically, you will boost their confidence and encourage them.

If you feel (or even know) that students have never experienced direct instruction with grammar, give them a pretest. You might need to start with complete basics (subjects and verbs, nouns and pronouns) and purposefully carry those terms over to other parts of class. For example when you teach a short story, emphasize proper and common nouns, pronouns and their antecedents, and verb tenses. A few extra examples provides students with the knowledge of domain-specific terminology.

I also address this first layer with simple posters. You could also make anchor charts and ask students to reference those terms or lists as you reference the posters. For instance when you are storytelling, you might point out proper nouns or interesting adjectives. The conversation should start naturally.

Be sure that you and your students share the same vocabulary with grammatical terms. After the pretest, review parts of a sentence or parts of speech with students. Later as you reach more difficult levels of Bloom’s, you’ll be glad you share terminology.

Finally, start small. If your students are not confident with grammar, pull out picture books and complete grammar one-pagers. Students can identify the terms in stories, and you can always use those one-pagers later for moving up Bloom’s Taxonomy. Sentence combining with a conjunction is a fun way to sneak in proper terminology.

Brief identification activities or exit tickets work too. Classes will start to remember the terminology.

Comprehension/Understanding

Understanding can be demonstrated in a grammar worksheet, but in no other section of my classroom do I only give students a worksheet. Grammar is no different.

When I am thinking beyond the grammar worksheet, I consider what I do with other material in class. The “understanding” portion of grammar lessons is the perfect opportunity to experiment with sticky notes, graphic organizers, pictures, and small group work. Here are two examples.

At this level, students should be able to recognize the terms, and a perfect opportunity to show their understanding is to add to the original posters or anchor charts you’ve already established. Have students add examples for each part of speech to display in the classroom display. Another way is to give each student a sticky note and have them add examples underneath the posters.

With prepositions, I show students various pictures. (The goofier the pictures are, the more involvement you’ll have.) Since prepositions show location, students can immediately succeed at using prepositions: around the box, under the box, atop the box. You can also ask students to find pictures to illustrate other parts of speech to demonstrate their understanding.

After students understand the terms, apply them to their reading by pointing out examples. (Continue doing this with other concepts.) You might check that students understand different and often confusing concepts, such as action and linking verbs.

You can also ask learners to draw conclusions from their writing to show they understand the grammar concept in question. At this point, you probably are seeing how to connect grammar and writing, especially with punctuation. For instance, when students create prepositions based on pictures, we finish the sentences. If a sentence begins with a prepositional phrase, we give it a comma. Eventually, our teaching grammar is advancing past knowledge and comprehension.

Application/Applying

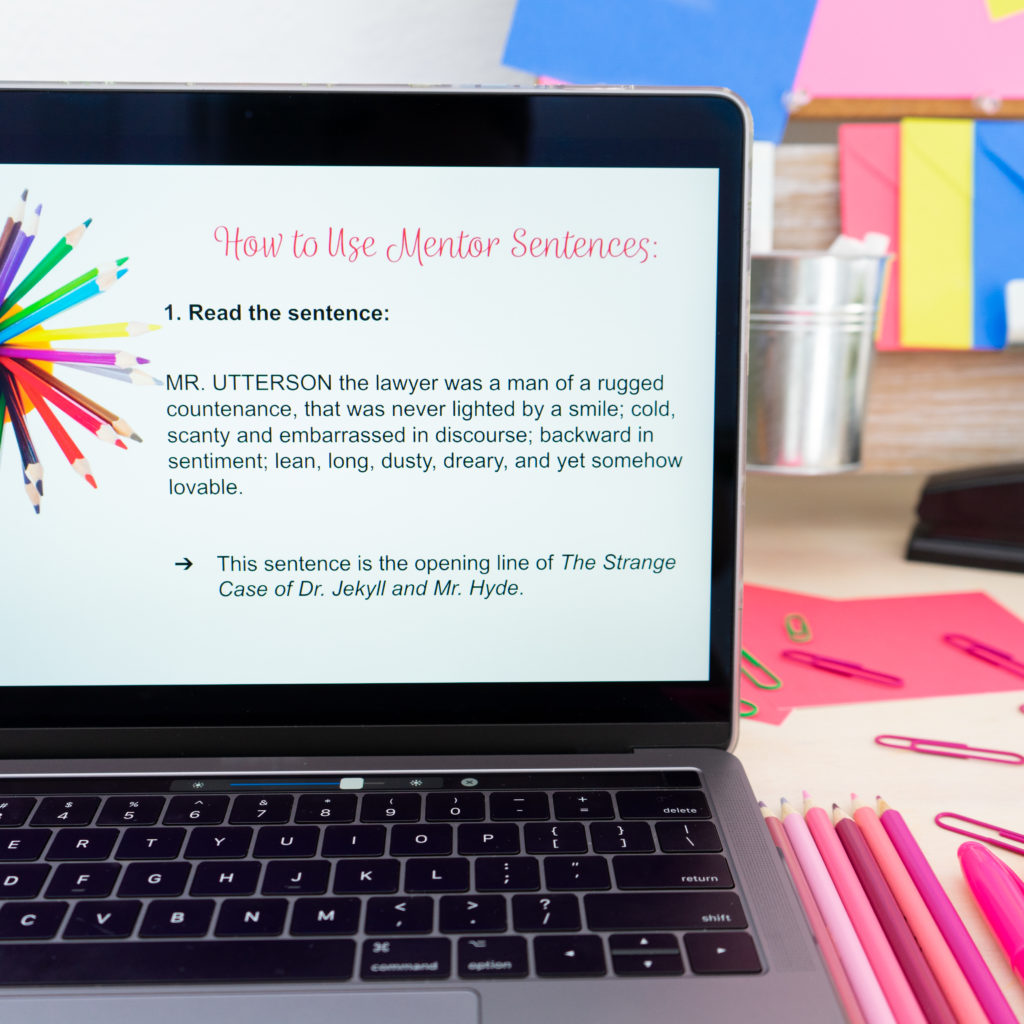

As you continue working with grammar, you’ll see openings for applying concepts to other areas of class. For instance, take two minutes of a literature lesson to apply a grammatical concept to literature. Ask students to demonstrate how the author used sentence structure to build suspense or how the author “broke” grammatical rules to improve their writing.

Another application concept connects grammar to vocabulary. Explain that parts of speech are used in different parts of a sentence. For example, a noun can be in the subject, direct object, predicate word, indirect object or object of a preposition position. If you are working with a noun (from a mentor sentence or from student writing), ask students to explain the word’s function and then change it. For example:

The light was not bright. (Bright is an adjective.) Could we make it an adverb?

The light did not shine brightly. Ask students which version they like better! By experimenting with language, you are empowering students to own their writing. You can also do similar practice with specific vocabulary lessons and more difficult words.

Finally, apply the knowledge of sentence structure (for example) with student writing. Ask students to determine what effect each sentence type brings to their papers. You can ask them to implement different phrases or modifiers in their writing too.

Build these ideas naturally, as the class sees them while reading and writing. Classes understand complex topics like grammar better when ideas are taught in context.

Once student see that your teaching grammar flows into other areas, they will realize that grammar is more than “catching errors.” Grammar is power.

Analysis/Analyzing

Solving language problems will be a large portion of analysis with teaching grammar. Punctuation is a large area that requires students to analyze their writing and determine proper punctuation. Show how punctuation rules work to make a text easier to read. So! Teaching grammar through writing is a elevated skill.

Provide direct instruction with whatever concept. . . like punctuation. Explain punctuation within quotation marks. Demonstrate the different uses for a semicolon. Analyze situations that provide contradictions and exceptions to rules. For instance, discuss commas and their tricks. Look at the debate over serial commas. Show students that grammar has leeway, and some ideas are debatable.

Another tool for analyzing grammar is a grammar sort. Google sorts are a fabulous way to categorize different concepts. At the end of a grammar sort, you can also draw conclusions about punctuation, review the function of the grammar concepts, and explain similarities and differences.

Chunking grammar lessons also helps with the analysis of language. When I taught test prep at a community college, the dean of my college specifically requested that we teachers chunk information for students. Since so much of English test prep deals with grammar, I naturally chunk grammar lessons. Here is a quick example of my thought process for chunking a grammar lesson.

When teaching sentence structure, I’ll break down certain components: subjects and verbs, relative pronouns, subordinating conjunctions, comma rules, and prepositional phrases. Sure, you know the prerequisites for sentence types, and you’ve taught them. You built the information on prior knowledge and scaffolded those grammar lessons. Still, you might need to chunk those components before covering compound-complex sentences.

Write each one of those sections on the board or give each section a Google slide. We’ll check off what we know about each concept and talk through them, adding as we work. Then, we will apply that chunked information to writing:

- Join a series with a coordinating conjunction in a simple sentence.

- Join two independent clauses with a coordinating conjunction to make a compound sentence.

- Join two predicates with a correlative conjunction.

- Join two independent clauses with a conjunctive adverb.

- Create a complex sentence with a subordinating conjunction.

I’ll continue working through different examples, drawing from the information that we chunked together.

Finally, language constantly evolves and changes. Many standards for the end of high school ask students to look at the larger picture of language and explain how language changes with society and culture. This change is evident with the discussion over the singular use of “they.” Review indefinite pronouns with students, and let them analyze (TONS of arguments exist online) and decide if this is simply language evolving or a mistake. Analyzing language can spark interesting discussions. Teaching grammar through writing allows for great discussions.

Synthesis/Evaluating and Evaluation/Creating

The top tier of Bloom’s Taxonomy entails my favorite parts of teaching grammar. At this point, students will differentiate between different grammatical parts and tear apart sentences to decide which subtypes these parts are. Rarely, you may need to return to memorizing charts as students’ knowledge of grammar progresses. For instance, students may recognize a word as a pronoun, but they will need to learn the difference between subjective, nominative, and objective pronouns as well as the singular and plural form of each. Knowing the type of pronoun will aid in understanding proper pronoun use, such as using the objective form for the object of a preposition. Again, reference those beginning posters. If you use the domain-specific vocabulary concerning grammar, you’ll spend less time on reviewing grammar and consequently, less time with grammar worksheets.

Students should evaluate their grammar in their own writing. Although connecting grammar to writing is not the only reason to teach grammar, it is an important reason. Students should apply sentence structure, punctuation rules, agreement guidelines, and verb mood rules to their writing. After you establish a firm foundation with grammar, you can then provide targeted practice to correct confusing aspects of student writing. By framing grammar lessons as tools for grammar, students are less likely to resent corrective exercises.

My favorite way to evaluate and create is with grammar manipulatives. Students hold language in their hands and follow different rules for using punctuation. They create sentences and evaluate the use of different conjunctions, locations of phrases, and use of verbs. Because we (as a class) have worked together, our community is strong enough to collaborate and invent goofy, creative sentences. Students start to see that grammar is fun.

Finally, encourage students to judge an author’s grammar. Should a writer have avoided passive voice? Does a certain story lack diverse sentence structure? Once students see that they should have an opinion about grammar, they’ll enjoy grammar lessons more and more.

Learning about grammar and language never ends because grammar and language constantly change. Teaching grammar through writing will emphasize all of your direct instruction. As you continue teaching grammar, students will recognize that grammatical formations differ enough to have different names. (A proud moment of mine is always when students realize that prepositional phrases have different functions without my prompting.)

As you move through Bloom’s Taxonomy while teaching grammar, you will find your groove. Begin adding more difficult grammatical sub-parts (such as verbals) as students show the ability to evaluate the basics and make informed decisions concerning syntax. Review the eight parts of speech as necessary and continue explaining grammar in all forms of communication.

Language arts classes too often lack the actual teaching grammar part of instruction. Knowing the foundation of a language provides learning opportunities beyond schoolwork. Grammar should not be taught as an individual unit of instruction. Instead, teach it every day so students realize it is part of their language, and that they DO understand it.

I hope this gave you some basics to incorporating grammar into your classroom and methods as you consider types of grammar activities. Grammar is my passion, and I hope this gives you a starting point with your classroom instruction. Please let me know if you used these ideas at all! I love to read real-classroom stories.