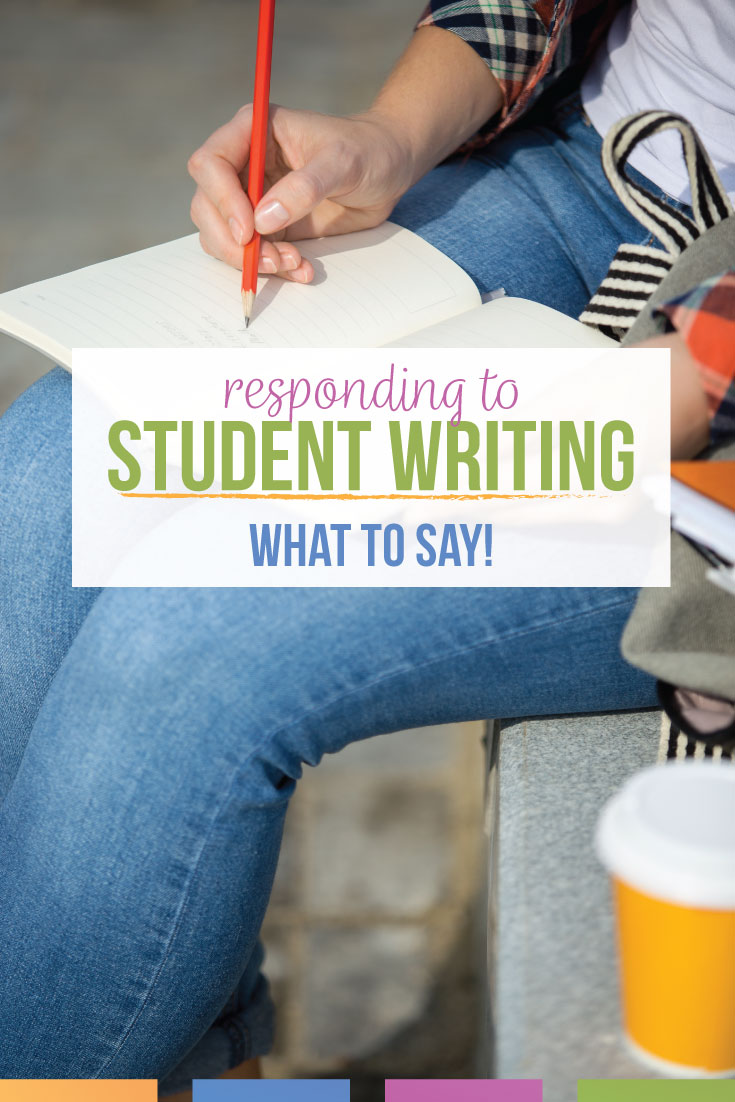

What can an English teacher do when responding to student writing? What teachers say matters, and we should consider their internal dialogue.

The more I teach writing, the more I consider student writing and internal dialogue. Students’ internal dialogue, not mine.

Grading student writing, I know how my internal dialogue runs:

I’ve taught this, right? I did a bad job teaching this. Grammar, agreement, comma splices, should I be using red ink? Purple? Would this argument make sense to another teacher? Am I doubting myself because I fear hurting a student’s feelings? Am I “sandwiching” feedback effectively? Is it fair not to point out these organizational errors? Am I preparing students for college? Will they be ready? Will they be able to effectively reply to emails at a job? Is this an effective thesis?

And on. So, my mind races as I grade writing. I feel immense pressure (as I’m sure other ELA teachers do), and I have developed coping methods for grading papers: checklists, batching, re-reads. As I continue teaching, I’ve learned to control my internal dialogue.

What I’ve realized is that what I say to students—what part of my internal dialogue is—becomes their internal dialogue. I need to be aware of my remarks. I’m aware that my remarks might become students’ internal dialogue.

For those reasons, I follow these simple guidelines when responding to student writing.

Preemptive commenting

Writing is a process, and it is more than the series of prewriting, drafting, and such. It is that, but writing includes exploration, frustration, and exuberance. Prepare students for that. Conveying one’s ideas is difficult. Learning how to successfully do so is a tough process. As the teacher, reassure students that you are there to help them with their learning process, all of it.

I use station work to model, circulate, and help students with their editing and revising process. I don’t hand students a checklist, but instead I ask direct questions for students to locate in papers. Students must work together and since they are in stations, I can intervene and help when students are confused or off task. I provide feedback, other students do, and I encourage the writer to provide feedback for their own paper. The commenting on papers becomes part of the process.

During writing, they will practice and collaborate. The feedback your provide students is merely part of the process. You’re traveling a road with students, guiding them along the way. Set up students to find your comments more helpful and less final. Stress that your comments are part of the learning process.

The more I explain that any feedback is merely part of writing, students not only become more agreeable to what I say, but they also are more likely to read the feedback.

Don’t be an editor

I edit with students as we read through their rough drafts. All the grammar errors—we work on those together. I try to catch and address most. Editing (hopefully) ends there.

If students turn in a final draft with editing errors, I make a note of what they should understand (agreement, complete sentences, capitalization). I don’t highlight every error. I want students to know a problem, but I don’t find every single problem. During conferences, I will address those troublesome areas and ask students to correct them. Sometimes, I break down one error at a time.

Be sure you have complete sentences. Then the student returns to me. Now, be sure that you use commas after introductory phrases or clauses. Then we focus on the next error, and on.

If I return a paper with every error highlighted and marked, students will shut down. They will be overwhelmed. Their internal dialogue will not set them up for success. Responding to student writing can’t look like that.

And? I don’t have time. I do something else instead…

Set goals

I help my students set goals for speeches, and goal-setting works well with papers, too. Teachers can easily differentiate and personalize lessons by setting goals with students.

Some students must focus on complete sentences while others improve pronoun use. Set a goal for a paper if you notice numerous problems while editing.

As students improve their writing, the goals might move away from mechanics. Organization or verb-use might become a larger focus. Meet students where they are with a goal. Goals that move past errors might include implementing strong transitions, varying sentence structure, or experimenting with a new technique like figurative language or pacing.

Hopefully, setting a goal and working toward it will become an automatic part of student dialogue.

Submit one sentence…

After students have a draft, I ask them to provide me with a sentence that they dislike. I typically have them digitally send them to me, and I provide feedback. Then, I ask students to apply the feedback to similar sentences.

One sentence? Yes. Students are less overwhelmed than if I graded an entire rough draft. Plus, this gives them the work, not me.

Also! I have interacted with each student, identified student-specific problems, and found class-specific problems. This leads to differentiated feedback.

Another take on the “one sentence” is for students to provide the class with their one sentence, for instance in a Google Form. Then, we work on correcting each one together. This method allows me to model sentence construction and thought processes for improving writing.

The other way I have structured the “one sentence” is for students to write their trouble sentence on a sticky note or piece of paper. I then ask other students to contribute. This really helps the feedback become a classroom effort. You can arrange the sticky notes in different sections of the classroom and get students moving.

“You have an opportunity”

The best wording for commenting on student writing? Point out where they have an opportunity for improvement.

Comments for student writing can point out opportunities for connections, improved sentence structures, or cultivated transitions.

“You have a real opportunity” to add stronger verbs, to focus your topic, to strengthen your transitions.

I don’t circle or underline every mistake, but rather I narrow down what students have an opportunity to correct. Mark up the entire paper? Students shut down. That approach might be necessary with some papers (scholarship applications), but with papers where students are honing their writing skills, a complete mark-down probably will not garner the results you want.

You want students to know you read their writing and took it seriously. You want to improve their writing and set them up for future success. Set the tone for accepting feedback, provide feedback as students write, and focus on their opportunities for growth.

Provide a big picture

What is right in front of students, at this very minute, might be what they are considering. Overall, of all the proposals, briefs, and emails that these young people will write in their lives, they are at the beginning of their writing careers.

Tell students that. They have many more years of building vocabulary and working on sentence fluency. Their teachers will help and provide support along the way. Writing is a team effort, and they will have many opportunities for practice.

Providing a big picture helps me to focus myself while grading papers. Students need a big picture so that idea becomes part of their internal dialogue. Students need to hear that they will write in their future careers and that their words have meaning. All of the “big picture” ideas help with student writing and internal dialogue. Even if they make errors right now (what writer does not??), those errors don’t define their writing careers. Students are writers, and they can grow as communicators.

Student writing and internal dialogue are linked. As much noise as I have in my head as I grade student work, I can’t imagine transferring that to students. When I reflect on grading writing in my earlier years, and while I know I had best intentions, I fear that I created hesitant and panicked writers. Students should (of course) take writing assignments seriously and be devoted to improvement.

My job as the adult should include guiding and pacing them, not creating a negative internal dialogue for them. As I am grading student writing, I am cognizant of how students might respond to my feedback.

What do you think of student writing and internal dialogue? Read what Melissa from Reading and Writing Haven discusses her ideas about student writing and their dialogue.