How to grade writing as an English teacher? It’s tough, and we might not finish quickly, but we can shave minutes off our grading time.

Two years ago, I wrote about saving time while grading writing assignments. I must feel the need for such a reflection at the end of every school year, because here we are again. . . discussing how to grade writing.

This is the end of about my tenth year as an English teacher (I was part-time for many years). In those ten years, I’ve sat down with thousands of papers to grade. When I first became a teacher, I’d sit down with the stack, normally a bowl of popcorn, and get grading.

Over time, this stopped working. One, my family grew. I can’t sit down at home and grade without my personal children climbing on me. Two, grading burnt me out. Three, I had to kick my leftover college-eating habits. (Studying and french fries turned into grading and popcorn. My older age is not allowing that.)

The process of how to grade writing that I had developed was failing me, so I changed. Grading secondary ELA papers this year has not been perfect, but I would count it as manageable. This outline (below) is the process I followed while grading papers. Feel free to follow or adapt it!

I read over each paper before “grading.”

I promise this shortens the amount of time it takes me to grade papers!

As the primary audience, I need to get a feeling for the papers. Before I make a mark on papers, I read them all first. This encourages me to look at students’ ideas and reflect as a reader—not immediately as a grader. (I believe there is a difference.)

It’s a quick read that provides me a “big picture” to decide where my grading and lesson plans should go next. Giving a quick read before marking provides me with an overall idea. Specifically:

- I can figure out if the rubric is fair and fix the rubric for next time. I might need to clarify a point if every paper missed it.

- I decide if I didn’t teach a concept enough. For example, maybe I never saw that students struggled with subject verb agreement or incomplete sentences. From smaller writing assignments, I maybe missed a large problem, and students need help.

- I plan what we’ll study next.

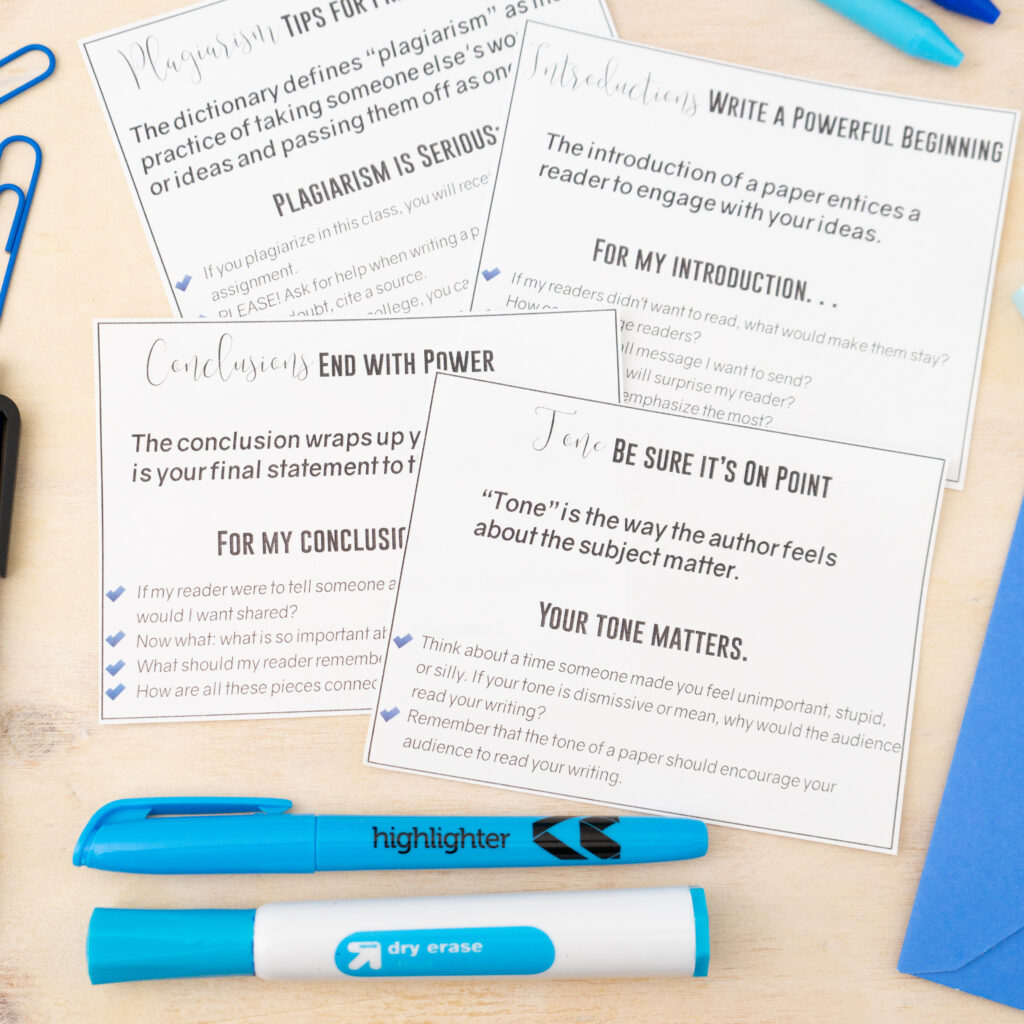

This “big picture” might work out to benefit students, but it might not. For instance with the last papers I assigned, I covered MLA format with specifics. Other times, I target introductions and conclusions., I hand out reminder cards (pictured below) that align with the rubric. That way if I see a student paper that needs work, I can conference, give the reminder card, and help the student correct the error. In the long run, the student has learned, and I have an easier time grading.

Still, still! Information was in the wrong spot, spacing was off, and on. It was a subject we (again) discussed as a class, but it didn’t change my grading of it. I know we covered it.

I work out my “mental” blocks.

Grading papers is tough. There are endless memes with ELA teachers as the target audience. Grading can be awful and defeating. It can seem never-ending.

First, I don’t grab thirty papers to grade; I choose a manageable number, like five. I tell myself that I will grade five papers and take a break. Then I sit my rubric and focus. At the same time, I don’t run to the coffee machine to take the break. I hold myself to the goal.

Second, I chop my activities into manageable pieces. All those brain breaks we are supposed to give students? Yeah, we need them too. After grading the five papers, I walk around, get the cup of coffee, or work toward another goal.

My largest mental block is feeling defeated with a heavy stack of papers on my lap. I give myself permission to take breaks and recognize my success (yes, grading five papers counts as a success) which beats my mental blocks.

I listen to my body.

First, I don’t snack and grade; I gained too much weight. What I learned was that if I was hungry and looking to snack, I was tired. Instead of eating my way through a pile of papers (and honestly, I wouldn’t make it because I’d get sleepy), I grab a glass of ice water. This wakes me and stops the fake-hungry pains.

Still hungry but I know I’m not really? I head to bed. I can’t give papers the attention they deserve if I’m exhausted. English teachers should not burn themselves out of the teaching profession as they are grading writing.

I schedule the grading.

When I leave work at the end of the day, I have goals for the following day. When I face a stack of papers, I schedule them into my day. I don’t avoid grading them, and I don’t assume I’ll grade them at home.

I will tell myself (sometimes I’ll even say it aloud to myself), that I will grade five papers at the start of my prep and two at the end. Sometimes, I write it down.

Adjusting writing lesson plans and tweaking the grading process never ends. I’m not sure it should. The way I would have described how to grade writing differs this year than it did five years ago. I imagine that in five years, I’ll have a more efficient process. My process for how to grade a paper evolves and reflects years of experience.

What about you? What grading process could you share to help other ELA teachers? If you need ideas for what to say to students about their writing, check out this post.

Are you looking for more tips for grading writing? Check out my Pinterest board, completely devoted to teaching writing.