Encouraging student reflections on the writing process can be a worthwhile process.

Applying reflective activities with whatever writing assignment can move classes toward student success. A powerful way to finish a writing project is with an overview of how their process went.

So much of what we do as writers and teachers of writing centers on reflection.

Student reflections on the writing process concerning:

- The finished process—the actual sitting down, the brainstorming, the doubts, the a-ha moments, and all the tears in between.

- The starting point—a blank page in a notebook or Google Drive.

- Painful cutting, erasing, deleting: I wrote this, and now it won’t work. Something is wrong, my message is not going through, or this product is not what I had in mind. But I wrote it—could it sound good? Eventually?

- A decision to be done. When am I ready for another person to look at my inner thoughts?

What questions surround secondary writing lessons and reflecting?

- How do I get students to authentically talk about their writing process?

- What sort of reflections will help students to dive into their writing?

- How can I provide encouragement with students?

Before I reflect on my methods with young writers, let’s consider research about reflecting.

Why reflecting in education matters.

Research shows that reflecting on your learning will deepen your understanding of that learning. The following quote from John Hattie is all over the web, quoted on Facebook, and made pretty with fonts on Instagram:

When teachers seek, or are at least open to, feedback from students as to what students know, what they understand, where they make errors, when they have misconceptions, when they are not engaged – then teaching and learning can be synchronized and powerful. Feedback to teachers helps make learning visible.

So when I think about reflecting on my teaching of writing lessons, I also consider the reflection piece that my students and I will engage in together. As we work on a piece of writing, I’m listening to students and asking questions and supporting them as they become writers.

My approach includes the foundation that I consider myself a writer, and I consider my students writers. I’ve written before about how I write alongside my students, Those concepts are intertwined: Student reflections on the writing process are authentic because everyone in the room (myself included) is writing. To get students authentically discussing their writing process, I often start with a common problem: a misunderstanding of how professional writers approach the writing process.

Our reflecting process starts with preconceptions about writing. As we write, what are we learning about incorrect assumptions?

Preconceptions about writers.

An honest class discussion of the writing process begins with what people think about the writing process. Often, students and I will brainstorm what they believe writers actually do. Years ago, I too believed many of these preconceptions about writers:

- Writers sit and write and a polished draft appears (grammar and punctuation perfect).

- And then, writers walk through the process, the entire writing process, and they finish it.

- Writers know what the finished product will be and produce it with minimal editing and revising.

Sometimes, movies and other forms of stories give people an inaccurate idea of what writing involves. Students might also just mentally “beat themselves up” over taking so long during certain stages of the writing process.

We start on the same page to start reflections. What sort of roadblocks have we thrown up that do a disservice to our writing? As we start with reflections on the writing process, we move toward understanding that writing is not linear—it is recursive.

Encouragement with young writers.

After considering preconceptions about who a writer is or what a writer does, we dive into questions and discussions. Along the way, I provide encouragement to young writers.

Students might be mentally disengaged from the writing process. Older students, especially, could be so accustomed to walking through the writing process that they might not consider ways to improve habits that hold them back, or methods that no longer serve them now or did when they were younger. Sometimes all writers hold onto parts of the writing process that do not serve them simply because those parts are habitual.

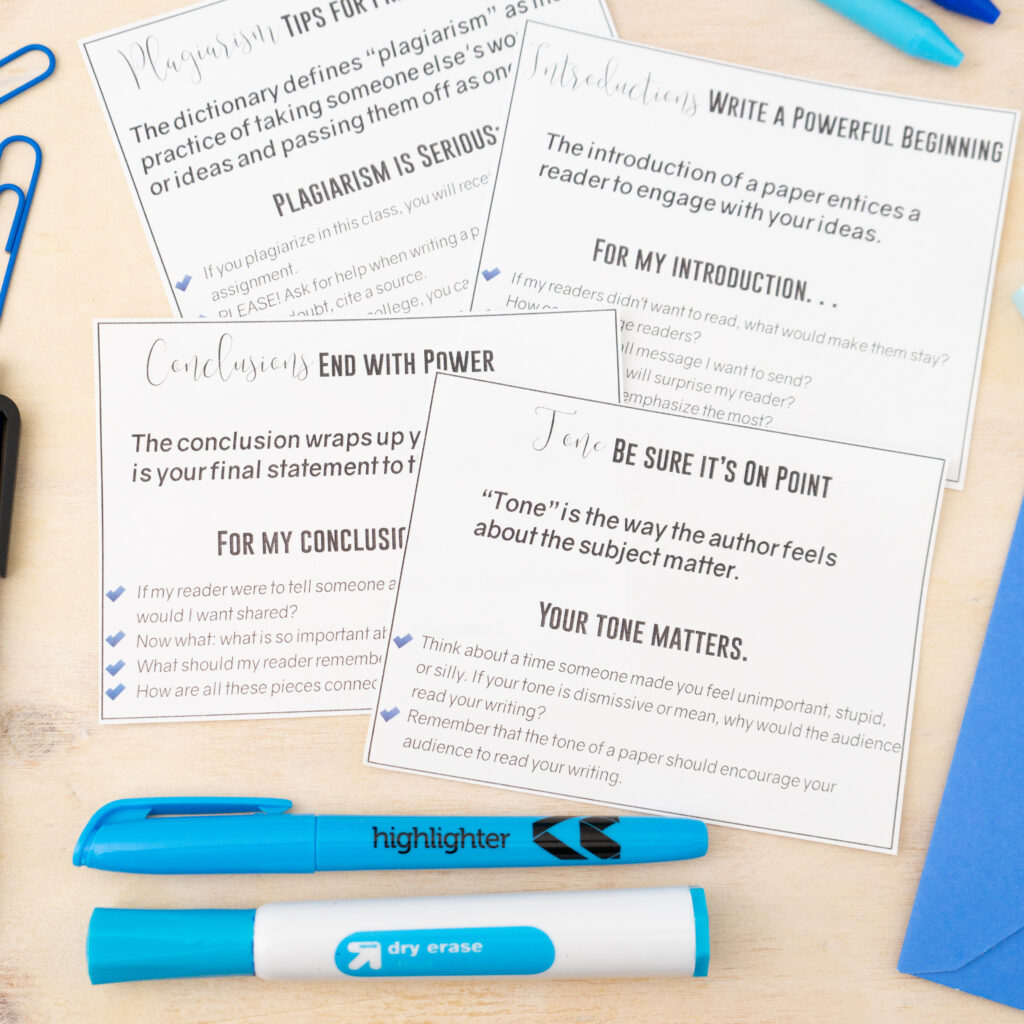

As we reflect on the writing process, we discuss several areas that could provide encouragement:

Did you discover your writing community?

A writing community helps writers. And? A community does not need to be a formal gathering. Asking questions, gathering ideas, and bouncing organizational structures off friends or family members can be an informal discussion.

Writing should not happen in isolation. Encourage students to find a community within or outside your classroom.

A baby draft is fine!

I reference the preconceptions about writing. Any form of a rough draft is a start. The first draft is simply that—the first draft that we can start with.

Again, I share with students my start which is almost always a list. I write down my topic, add any idea that enters my head, and then write some verbs that might align with the topic. Will that be everyone’s prewriting to turn into a draft? No, and in fact, it shouldn’t be. Older students probably have some sort of method that works for composing that first draft.

My first draft is also messy and incomplete. I might have a topic sentence, one piece of analysis, and then realize I need to look at my prewriting again. I share that experience with students so that they realize this is not a sign of failure. Instead, I mentally understand that my list helps. As I draft, I rely on my first ideas. Additionally, I know my first draft is nowhere near publication.

Look at procrastination in a new way.

Most people procrastinate in some form. Why? Students can reflect on procrastination so that they can tinker with their processes to get more done. I procrastinate too, but I have tweaked my procrastination to move past it. And—I share how I don’t let procrastination affect my well-being, how I don’t allow it to stall my writing process. I clean my kitchen, and students often share that they clean their rooms.

What do I do with my procrastination and my clean kitchen? I added a notebook to that part of my writing process. While cleaning I think through ideas. I jot down my brainstorming, favorite words that will help to build my point, or ideas that might never connect to my paper, but won’t leave me alone. . .

Sometimes, young writers who reflect on their writing processes want to know they are not alone. I joke that cleaning the kitchen has become an important part of my writing process. The encouragement from my honesty (with struggles and successes) spurs them onto reflection.

Authentic talk.

Working with young writers often requires a thirty minute discussion )or so) to reflect on their writing process. After discussing preconceptions, I start with a simple question: What specific part of the writing process are you most proud of? When posing this question, I find students don’t merely say their final draft.

Often, students note their use of a graphic organizer or work with a peer reader. They are proud that they made an outline, found a suitable piece of research, or discovered interesting transitions. To reflect on those successes, we discuss what went well, why those moments clicked, and how we can repeat them.

Most of whatever students found from the writing process that worked was empowering to them.

Keep moving with that discussion—find where can more empowerment take place with the process.

Like my kitchen cleaning whilst brainstorming (as part of my first step), I know what will work for me. As I continue posing questions to my students, walking through their processes with them, and modeling reflections, we move toward authentic reflections.

Student reflections on the writing process can become a part of your secondary ELA writing lessons. I hope my process gave you ideas today.