Understanding language and moving past grammar lessons: can we make the switch? Teaching language standards provides a new frame for discussing grammar.

The more I write about grammar and read research about the teaching of grammar, the more I am convinced that we ELA teachers should reference understanding language with students and in our planning. As we know, grammar is under the language standards, and this emphasis frames grammar positively for students.

In this post, I aim to explain how we can make the switch to language lessons and how this shift will help our students understand the english language. I included tons of resources for you, and as always, you can find them in my library.

Additionally, this approach is particularly beneficial for ELL students, as it supports their understanding of the language. With my professional development concerning multilingual students, I understand the importance of mentioning domain-specific language, of talking with terms naturally.

What English language standards am I referencing?

I teach in Illinois, so I do use Common Core State Standards. No matter where you teach, I understand (from professional learning opportunities) that standards ask students to have a deeper understanding of language, more than simple identification.

Also in this post, I’ll reference mentor sentences. I know that hundreds of my blog readers use that tool to meet eighth, ninth, and tenth grade language standards. You can use my presentation of mentor sentences, or you can crate your own. My examples from this post come from that presentation.

So, why do I think we should make the switch from “grammar” to “language”? Understanding language meets standards, engages students, and helps students retain information.

Below are my ideas for teaching language standards to all learners.

Are you using domain-specific language while talking?

Think of a concept your students understand well, something you and they discuss with confidence.* For some teachers, language arts students might discuss literary devices with ease. Other classes might understand text features especially well.

No matter the domain-specific vocabulary, you and your students talk with those terms. For instance, students might understand “theme.” They can write about contributing pieces from a story that create the theme. Maybe they confidently pull quotes that support the story’s theme. They can debate a story’s theme. When they read a nonfiction article, they might realize that the author slowly built a them. As students write, they might attempt to incorporate a theme into their paper.

Students use the term “theme” in many situations. They try it on—experiment with it. Maybe, they use it incorrectly, and you explain the nuances so they get it right.

We can model language about language the same way!

Do you use language terms the same way you use other terms? For instance, do you and your students discuss:

- Connotation and denotation

- Action and linking verbs

- Parallelism

- Clauses

naturally? Outside of grammar lessons? Spontaneously?

For students to own domain-specific vocabulary, they should use it in a variety of ways. Only using grammatical terms during grammar lessons won’t help students carry over that language into other parts of class. We should incorporate language and its vocabulary as we do terms like communication, conflict, and thesis.

Why mentor sentences for learners?

I teach grammar in a variety of ways—the same as I teach another other topic in my classroom. Yes, I use worksheets and direct instruction. I also use word walls, graphic organizers, videos, and grammar sorts. Honestly: teaching language standards is tough. Those standards are difficult, so I approach them in new ways.

A goal of language lessons is to connect the domain-specific vocabulary to other concepts in class, and mentor sentences accomplish that goal. With mentor sentences, I can nudge students past identification and toward analysis, maybe even evaluations. Mentor sentences provide a suitable way to meet language standards.

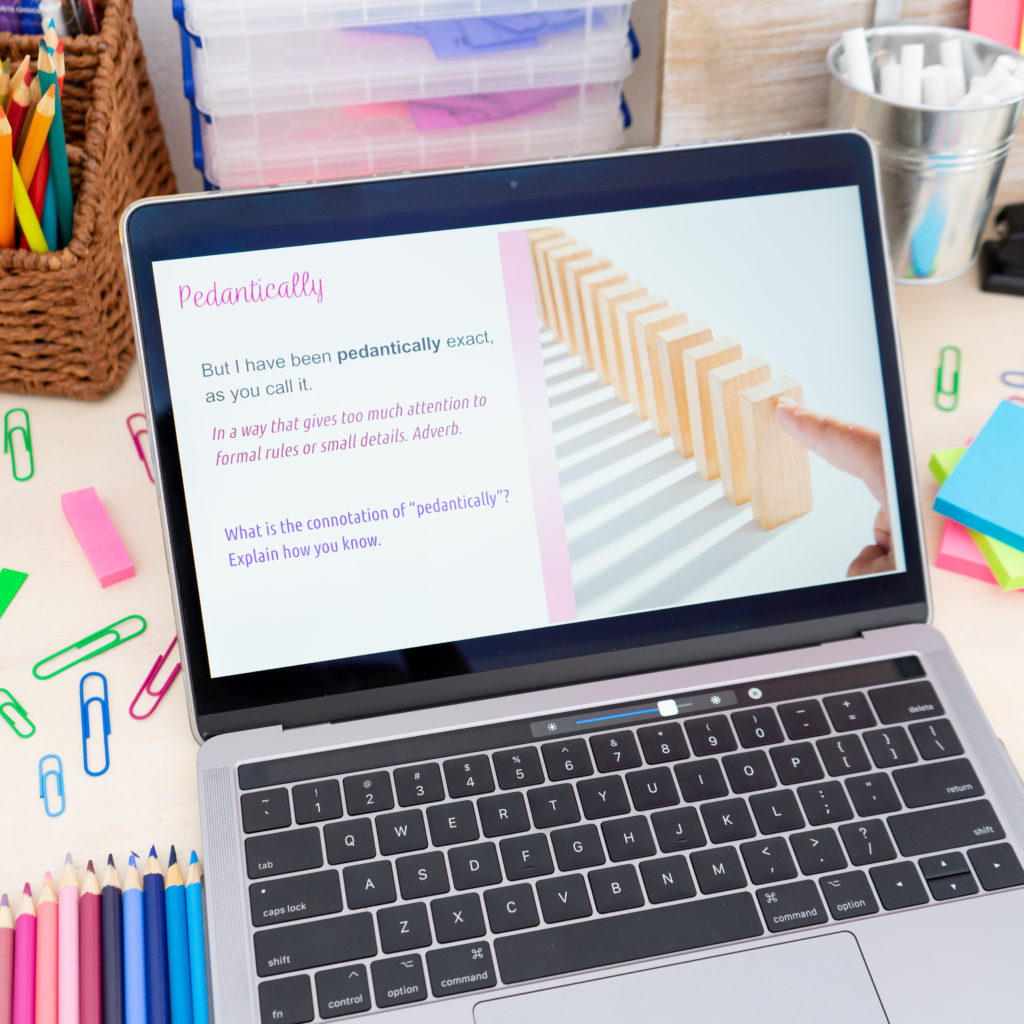

The above mentor sentence provides opportunities to meet language standards. For instance, language standards ask students to grow their vocabulary and to understand the connotation. Is understanding “pedantically” a grammar lesson? Maybe! More specifically, it is a language lesson. Ideas for working with the word “pedantically” might include:

- Asking students to recognize the denotation and then to discuss the connotation.

- Recognize that the word is an adverb, but students can use it in a sentence as an adjective. Work with students to use the adjective form NOT as a predicate adjective (He is pedantic).

- Find their own picture to understand the definition.

- Evaluate the author’s use of the word. What word would modern audiences use? (This sentence is from Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. Using an older mentor sentence provides the perfect opportunity to discuss how language changes.)

Those questions are simple examples of how you can implement domain-specific vocabulary into language lessons, to move lessons past simple grammar lessons.

How can I start teaching language standards?

You might think, sure! Yes, using specific language in a variety of ways with grammar lessons will help me teaching language standards. Thinking of “language” instead of only “grammar” might help too, but I’m nervous.

Stepping outside our normal lessons can be difficult, but our students will benefit. Plus, if we look at language standards, you can see the need to incorporate this domain-specific vocabulary across class, not only during a grammar lesson.

Take baby steps with language standards.

First, don’t be ashamed to review. Grab a textbook or some worksheets. Find an online grammar quiz or some videos. Take notes over grammar and language concepts. Think: If you had not taught British literature in years, you would review periods and movements. You would brush up on the authors, right? Review difficult concepts with grammar and language. That does not mean you are not a good teacher!

Second, don’t think that students can’t or won’t retain domain-specific vocabulary. So often, teachers confide in me that they teach grammar doesn’t stick. Students will remember grammar if they use the concepts in a variety of ways.

Finally, these goals require us to stop the teaching of grammar as only something wrong with student writing. (Who wants to study something that only shows what is wrong with a huge project?) Teaching language requires a shift. “Grammar” is more than errors. Understanding language, including sentence structure, provides a foundation students can use with reading, writing, and speaking.

What about higher-order thinking with language?

You can download my free teacher sheet for advancing student thinking about language. This sheet provides guidance for teachers as they provide feedback. If you are looking to move beyond the standard “comma splice” comment, this sheet provides concrete ways to move students toward that higher-level of thinking.

As you provide modeling for domain-specific language verbally in class, add these comments to students’ writing feedback too. Plus, the sheet encourages students to recognize what they do well. Grammar is so much more than what is wrong with writing. It is about understanding the intricacies of language and using it effectively in all aspects of communication.

Final ideas for understanding language with students!

Owning an understanding of language is more than checking a box with grammar. Language standards provide opportunities for domain-specific vocabulary and to treat grammar and language simply as we do any other topic in an ELA class.

Shifting from grammar lessons to understanding language will take time, but I think that the words and ideas surrounding grammar must change. When language arts teachers present grammar as a problem to solve rather than a tool, rather than understanding language, we are missing an opportunity to help young writers and learners.

*From my understanding, science standards, including Next Generation Science Standards, emphasize domain-specific vocabulary too. In connecting with parents and guardians, it might help to mention that connection—that diverse organizations want students using the vocabulary of each class.